| Children

of Clay

by Ed Thomas, Ed.D.

Iowa K-12

Health and Physical Education Consultant

|

|

Naturam

non vinces nisi parendo |

|

“You will not master Nature

unless you obey Her,” said the

Ancients. We must conform to Her fixed

and indisputable laws to live in harmony

with Her. Follow Her rules, and we

will grow beautifully formed. Disobey

Her, and She will deform us.

One of our

best historical models for living

compatibly with Nature is the Ancient

Greek. Discipline, symmetry, beauty,

strength, endurance, agility, and

graceful harmony were admired, sought

and often attained. The Persian Wars

brought continued urgency and personal

responsibility to Greek physical culture,

and athletic games provided opportunity

to put aside mundane strife in favor

of activities more transcendent in

form and nature. Thousands of years

later, the Ancients still offer us

a compelling and rational paradigm

for physical education.

From the Ancient

Greeks, we are taught to see the human

organism as a temporary vehicle through

which divine unity and its subordinate

stages can be sought, experienced

and celebrated. The beauty of their

language frees us from the decay of

our own. Their art provides an ideal

of the human form. The crumbling statues

from their vanished cultures remind

us that we too will be dust, and precious

life should not be wasted on anything

less than the pursuit and love of

truth, beauty and wisdom.

From the historical,

linguistic and sociocultural high

ground, the physical

|

educator’s

responsibilities are enormous.

"Nations have passed away and left

no trace, and history gives the naked

cause of it,” wrote Rudyard Kipling.

“One single, simple reason in all

cases; they fell because their people

were not fit." Physical fitness includes

physique, organic function and motor

skills. All of these are impacted

by posture and body mechanics. Physical

educators are the first line of defense

against the unnatural influences that

would deform our children. We are

charged with guiding their motor development

across the precarious bridge between

childhood and adolescence. By the

post-secondary level, we should be

helping them add the final touches

to their symmetrical, proportional

and highly efficient forms.

This is the ideal.

|

| Ill-fitting

furniture including flat desks

are a crime against children

and youth.

This is clearly a physical education

issue. |

|

Page

1

|

The

reality is that postural deformities

and poor body mechanics are epidemic.

Our precious youngsters are growing

steadily more inert, malformed and

clumsy. Fortunate are those who survive

the education gauntlet with minimal

damage and defects. It is not for

a lack of historical evidence that

we fail to effectively address the

importance of good posture and body

mechanics. It simply fell off the

radar. Throughout the K-12 experience,

youngsters fully capable of being

taught to move gracefully and efficiently

are victimized by an educational system

that reinforces poor posture and body

management skills. Probably more a

crime of omission than commission,

it remains to be seen whether the

paradigm will shift.

Posture can

be simply defined as, “Any position

in which the body resides.”

Good posture is a rational adjustment

of the various parts to each other

and of the body as a whole to its

environment, task or work. The complex

human organism is constantly in motion,

so our posture is continually shifting.

Body mechanics is posture’s

close relative.

In 1932, the Orthopedics

and Body Mechanics Subcommittee of

the Hoover White House Conference

on Child Health and Protection defined

body mechanics as "The mechanical

correlation of the various systems

of the body with special references

to the skeletal, muscular, and visceral

systems and their neurological associations.”

In other words, good posture and body

mechanics are the foundations of motor

development. If we taught nothing

else, these would stand first in line

for attention.

Ptosis (drooping

or falling) is one of the primary

problems associated with poor posture

and body alignment. Skeletal ptosis

manifests as a forward dropping of

the head and variousunnatural

spinal curves with rotation and displacement.

Visceral ptosis

is another common condition where

an organ or organs are |

displaced

downward.

The common hyperflexed slump seen

among our children and adults displaces

the lungs, heart, liver, intestines,

and other vital organs. Exterior structural

adaptations and indicators often include

rounded shoulders, a flattened chest

and protruding abdomen. Blood ptosis

is a downward displacement and collection

of blood in the splanchnic veins of

the abdomen caused by insufficient

nervous control of the splanchnic

veins that must work against gravity

to do their job. Weak abdominal muscles

contribute to the problem.

|

Ptosis

is a common, unsightly

and preventable postural deformity. |

|

Page

2

|

| Occupation,

disease, poor care in infancy, and

malconceived physical education curriculums

are a few of the obvious influences

that can impair postural development.

Other subtle and overlooked factors

such as ill-fitting school furniture

and extensive practice of specific

sport skills early in life have not,

in the recent past, been widely acknowledged.

Overall, a complex set of issues involving

heredity, environment and habits must

all be considered, but one of Nature’s

most important realities is that gravity

molds us.

We are living clay, and Nature’s

gravity is like the potter’s

hands molding and shaping us. To exist

in harmony with Nature, we must also

live compatibly with gravity. One

of the most enduring explanations

for our troublesome relationship with

gravity is that our ancestors were

quadrupeds. Somewhere in history,

the theory goes, we decided to stand

our quadruped skeleton up on its hind

legs. With all its benefits, the upright

bipedal posture presents some serious

kinesiological challenges. Our many

moving parts must constantly seek

a center of gravity to avoid unwanted

stress and strain. This requires tremendous

muscular balance and neural coordination.

Slight misalignments anywhere in the

system create imbalance throughout

the organism, and a pernicious cycle

of structural and functional defects

follows. A return to all fours is

not a popular option, and not everyone

agrees that postural deformities and

the suffering that accompanies them

are the price we must pay for walking

on our hind legs. Dr. Robert M. Martin

challenged the evolutionary theory

of postural develop |

-ment

in the early 1960’s, and his

insights are still worth considering

today.

Martin was born and spent his childhood

in central Iowa during the early 1920s.

His father was a chiropractor. Martin

began training in the German system

of gymnastics when he was around five

years old. As a young man, he worked

with Bernarr McFadden and taught at

Turner Halls in Philadelphia and Kansas

City. Martin eventually received degrees

in Chiropractic from National College

in Chicago, Osteopathy from the College

of Osteopathic Medicine in Kansas

City, and Medicine from the California

College of Medicine in Los Angeles.

|

| Young

Martin, on top,

was anaccomplished gymnast. |

|

Page

3

|

Martin

began specializing in orthopedics

early in his career, combining the

healing power of movement to his medical

treatments. Martin eventually migrated

to Southern California, and was there

in the early 1960’s when a new

national interest in physical fitness,

weight training and gymnastics was

ignited under the leadership of President

John F. Kennedy. Martin’s ideas

began to appear in California-based

health and physical fitness magazines.

From his clinic in Pasadena, he combined

decades of medical studies with the

lessons he had learned as an Iowa

gymnast, relying heavily on the power

of rational movement to heal his patients.

In his 1975 book, Cum Gravity—

Living with gravity, he wrote, “Being

a physician who also practices and

teaches gymnastics, one discovery

became most pronounced to me. I found

that my avocation was often helping

people far more, in many ways, than

my vocation. It was something of a

miracle to see the wonderful transformation

of ailing men and women into persons

of commanding physique and stamina;

some of these were individuals who

at the beginning of their exercise

programs seemed most unlikely to improve.”

Martin also questioned the common

mainstream assertion that humankind

is ill-equipped to walk upright. He

wrote, “Hundreds of volumes

(books, newspapers, magazines, etc.)

have been published on backache. Almost

all authors of these articles have

a single premise: an assumption that

low-back pain has plagued mankind

ever since man assumed the unanimal

like posture of the human when he

changed from a quadruped to a biped. |

They

relate that at the time this change

occurred, man's neuro-musculoskeletal

mechanism was that of a quadruped,

and that as bipeds, our bodies are

unable to live compatibly with gravity

to this very day.

It is declared that because man stands

erect, his spine is unstable and gravity

has devastating effects - not only

on the vertebral column, but also

on many other body functions. Thus,

gravity is proclaimed to be man's

foe.” Martin challenged the

notion that gravity is the villain,

and humankind is doomed to ultimately

be compressed and distorted by its

unidirectional force and relentless

pressure upon us. He argued that we

do it to ourselves because we limit

our motion. Martin wrote, “In

the development of life on earth,

no force is of greater consequence

than the force of gravity. This force,

without the intelligent use of exchange

of postures, can deform, disable,

or even destroy your body.

Gravity applies its constant, relentless

force to the pliable, moldable, movable

structures of the body, much like

a potter manipulates and molds clay.

The resulting shape depends on how

the force is allowed to apply. In

both cases, to produce a shape and

form of beauty, intelligent application

of force is required.” Martin

suggested that there are six basic

human postural categories. Three of

them are common. Most people spend

their lives, twenty-four hours a day,

in them. The other three postures

are uncommon. The common postures

produce compression and shortening

of stature while the uncommon postures

decompress and elongate. In other

words, the uncommon postures are compensatory.

They mitigate the wear and tear caused

by constantly assuming the dominant

common postures. |

Page

4

|

Martin’s

six basic postures illustrate

the importance of postural exchange.

Group I - Common Postures

Effects: Produce body compression

and

shortening of stature.

Used: In work, play, rest, etc.

1. The ERECT POSTURE (Fig. 1)

(The posture of Dominance)

a. Sitting

b. Standing

2. The HORIZONTAL POSTURE (Fig. 2)

(The posture of neutrality)

a. Lying (On side, back, or front)

3. The FLEXED POSTURE (Fig. 3)

(The posture of Accessibility)

a. Bending forward

Group II - Uncommon Postures

Effects: Produce body decompression

and elongation of stature.

Used: To counter and correct adverse

effects of gravity produced by the

common postures

4. The EXTENDED POSTURE (Fig. 4)

(The posture of Bending Backwards)

5. The BRACHIATED POSTURE (Fig. 5)

(The posture of hanging by the limbs

- upper or lower)

6. The INVERTED POSTURE (Fig. 6)

(The Upside-down Posture)

a. Hand Stand

b. Forearm Stand

c. Shoulder Stand

d. Hanging by the Lower Limbs

|

|

Martin’s

six basic postures illustrate

the importance of postural

exchange. |

|

|

| Yogis

and Monks have

inverted for centuries. |

Martin

began inventing inversion equipment

early in his career, but he was always

quick to give credit to others who discovered

the principles before him. Yogis and

monks have inverted for centuries. Physicians

in the Middle Ages used the Scamnum

Hippocrates. It was a ladder-shaped

bed used to facilitate inverted traction.

|

| Physicians

in the Middle Ages

employed the Scamnum Hippocrates. |

|

Page

5

|

In

the late-1800’s, the great Strongman

C.A. Sampson advocated the Roman Column.

The famous body builder John Grimek

trained upside down in the 1940’s

and 50’s. Joseph Pilates also

used extension, inversion and brachiation.

Many chiropractors and physical therapists

have used extension and inverted brachiation

for decades. Physical educators are

beginning to recognize the value of

postural exchange, but mistakes in

methodology can be at the expense

of students.

|

|

Body

Building legend John Grimek

lifted light weights while inverted. |

|

| |

| The

great 19th

Century strongman C.A.

Sampson used the Roman Column. |

Page

6

|

Once

deprived of the uncommon postures

over time, spatial awareness deteriorates.

Students and teachers must be taught

to safely and profitably enter, assume

and exit these uncommon postures.

Progression, variety and precision

are essential, as is correct spotting

and instruction.

|

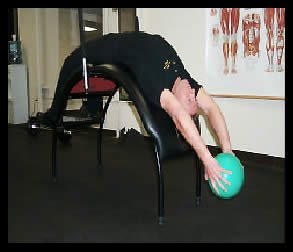

LTC

William Rieger, Commandant

of

the United States Army Physical

Fitness School demonstrates

horizontal

extension on a Body Bridge. |

Many

physical therapists and physical trainers

have also recently rediscovered extension.

In the early 1980’s, leaning

backward was widely discouraged. Critics

frequently called it hyperextension

to stress its negative nature. Innovations

such as the popular Swiss ball, Body

Bridge and numerous other extension

devices now provide tools to safely

teach and practice it. Unfortunately,

it is not uncommon in our universities

today to still hear professors of

exercise science or physical education

warning against extension. Inverted

postures like handstands, shoulder

stands and forearm stands are also

often contraindicated or simply overlooked.

Inversion tables and boots were generally

ignored or deplored by most physical

educators when people |

across

the country started using them in

the early 1970’s. Many physical

educators based their opinions on

1980’s research that warned

against turning the body upside down.

Herbert Devries, Ph.D. put the exaggerated

risk of increased arterial blood pressure

and cerebrovascular damage caused

by inversion to rest in 1985 when

he wrote; “Considerable valid

research data on the use of inversion

devices to relieve low back pain have

been published in the medical literature.

Unfortunately, the information has

been distorted and sensationalized

in the lay press, giving rise to confusion.

With proper precaution, full inversion

using an oscillating inversion device

probably presents no risk to normotensive

healthy persons.”

|

Thomas

teaching inversion

to students at The University

of Iowa in the early 1970s. |

I

began teaching decompression and mobilization

in physical education skills courses

at The University of Iowa in the early

1970’s. Using a device called

a Physicare Machine and later Dr.

Martin’s equipment, I safely

introduced hundreds of students to

a variety of inversion techniques.

Some faculty members were at best

ambivalent about the concept. One

anatomy professor wrote, “I

doubt this does much good but in all

fairness I’m quite sure it probably

doesn’t hurt anything either. |

Page

7

|

In

fact, a little stretching each day

undoubtedly feels good, if one wants

to do it this way that’s their

own business. More power to them—but

don’t pay anything for it.”

Not all physical educators ignored

or rejected Martin’s methods

during those years. In a 1986 letter

to him, past president of the AAHPERD

and a former professor at The University

of Iowa B.D. Lockhardt wrote, “If

the AAHPERD embraces the concepts

you teach and modifies its fitness

assessments accordingly, every child

in physical education classes throughout

America will be positively affected

by your ideas. I am hopeful that we

will make these adjustments as soon

as possible and start on a steady

and sensible program of preventing

back pain long before it starts.”

|

| Thomas

facilitates

inverted brachiated extension

at

Northern Illinois University. |

|

I

introduced Martin’s theory of

six postures to thousands of students

at Northern Illinois University between

1979 and 1993. I taught students in

Korea, Germany, Burma and Thailand

to invert, extend and brachiate. Most

recently, I worked with the United

States Army to implement inversion

Army- wide. First tested by U.S. Army

Rangers in the mid-1990’s, the

United States Army Physical Fitness

School now recommends inverted decompression

and mobilization as an integral part

of physical readiness training for

all U.S. soldiers. After almost thirty

years of teaching people to employ

these simple but uncommon postures,

it remains for me a mystery that such

obvious principles of posture and

body management are not widespread

and mainstream practice.

|

| United

States Army Rangers practice

inverted sit-ups at Fort Benning,

Georgia. |

Martin’s

message is uniquely suited for our

time, and we are wise to again consider

the complicated notions he eloquently

translated into simple andcompelling

language. “Examples of the consequences

of not living compatibly with gravity

and Newtonian Law are found everywhere,”

He wrote. “One needs only to

look at his neighbor and his drooping,

shortening, sagging stature; bulged

out mid-section, and unsightly posterior

to see the devastating |

Page

8

|

effects

of gravity, illustrating how important

it is to live compatibly with this

major environmental influence. Too

many of us are models of molding tissue

living without concern for gravity's

guiding power - a power we must learn

to respect and use positively. The

body is not only molded by the force

of gravity, but it is conditioned

by it. Gravity has been cast in the

role of a villain instead of being

seen in its proper light, namely a

servant of mankind. It is the limiting

of motion and fixation of posture

that allows the force of gravity to

warp the body and thus cause common

backache.” There is, of course,

much to consider if and when the physical

education profession begins to rebuild

the posture and body mechanics curriculum.

Martin’s pioneering work can

certainly provide a start point, but

many others past and present have

dedicated their professional efforts

to these issues. If and when we decide

to develop posture and body mechanics

curriculums that actually make a difference

in our students’ lives, we will

be pleasantly surprised that much

of the work has already been done

by those before us who lived close

enough to Nature to see the simplicity

and logic of Her eternal laws. To

reach Ed Thomas, Ed.D. at the Iowa

Department of Education, call 515-281-

3933. Website www.ihpra.org. Recommended

Sources

1. Bennett, H.E. (1928). School posture

and seating. Boston: Ginn and Company.

2. Devries, H.A. (1985, October- November).

Inversion devices: Potential |

benefits

and precautions. Corporate Fitness

& Recreation, 4 (6), 24-27.

3. Drew, L.C. (1927). Adapted group

gymnastics. Philadelphia: Lea &

Febiger.

4. Drew, L.C. (1929). Individual gymnastics.

Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

5. Goldthwaite, J.E. (1934). Body

mechanics. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott

Company.

6. Howland, I.H. (1936). The teaching

of body mechanics. New York: A.S.

Barnes.

7. Jacobsen, E. (1929). Progressive

relaxation. Chicago: The University

Press.

8. Lee, M., & Wagner, M. (1949).

Fundamentals of body mechanics and

conditioning. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

9. Lippitt, L.C. (1923). A manual

of corrective gymnastics. New York:

The Macmillan Company.

10. Lovett, R.W. (1922). Lateral curvature

of the spine and round shoulders.

5th ed., Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s

Son and Company Incorporated.

11. Lowman, C.L., Colestock, C., &

Cooper, H. (1928). Corrective physical

education for groups. New York: A.S.

Barnes and Company.

12. Martin, R.M. (1975). Cum gravity-

Living with gravity. San Marino, CA:

Essential Publishing.

13. Martin, R.M. (1979). The gravity

guiding system-Turning the aging process

upside down. San Marino, CA: Essential

Publishing.

14. McKenzie, R.T. (1923). Exercise

in education and medicine. Philadelphia:

W.B. Saunders Company.

15. Mesendieck, B.M. (1931). It’s

up to you-The Mesendieck system. New

York:

36 West Fifty-ninth St. |

Page

9

|

16.

Metheny, E. (1986). Movement and meaning.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

17. Pearl, N.H. & Brown, H.E.

(1919). Health by stunts. New York:

Macmillan Company.

18. Rathbone, J.L. (1934). Corrective

physical education. Philadelphia:

W.B. Saunders Company.

19. Richardson, F.H., & Hearn,

W. J. (1930). The preschool child

and his posture. New York: G.P. Putman’s

Sons.

20. Spencer, H. (1886). Education:

Intellectual, moral, and physical.

New York: Appleton.

21. Staley, S.C. (1926). Calisthenics.

New York: A.S. Barnes and Company.

22. Sumption, D. (1929). Fundamental

Danish gymnastics. New York: A.S,

Barnes and Company. |

23.

Stafford, G.T. (1928). Preventive

and corrective physical education.

New York: A.S. Barnes and Company.

24. Thomas, E.J. (1993). Decompression

and mobilization-Down but not out

of the gymnasium. The Physical Educator,

50, 39-46.

25. Thomas, L., & Goldthwaite,

J.E. (1922). Body mechanics and health.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

26. Todd, M. (1937). The thinking

body. Boston: Charles T. Branford

Company.

27. White House Conference. (1932).

Body mechanics in education and practice.

Washington: Library of Congress. |

Page

10

|

We

would like express our appreciation

to Ed

Thomas, Ed.D for

this excellent article and permission

to present it on ww.energycenter.com.

Dr.

Thomas has

been doing amazing work in the field

of health and fitness for decades.

If

you would like to visit his website

please click

here: |

|

Why

do some doctors advise against

inversion therapy?

|

| For

centuries traction had been

one of the primary doctor

prescribed therapies for back

problems. Recently pain medication

and surgical treatments became

popular. Even though traction

was recommended for centuries

sometimes modern doctors will

advise against inversion therapy.

It has been our experience

that one

of the main reasons they advise

against inversion is because

they do not understand that

the user has total control

over the angle of incline

and extreme angels that may

concern the physician are

not recommended nor are they

usually necessary for achieving

great benefits. What some

doctors need to realize is

that a person can set the

table for horizontal or any

mild degree of incline. When

very mild angles are used

the stresses on the body are

minimal and any risks are

reduced. We have heard from

people over the years who

avoided inversion therapy

because their doctors did

not understand the potential

benefits. Some of these people

found a different doctor who

did understand how much benefit

could be achieved with as

little as 15-20 minutes a

day of mild inversion and

rhythmic intermittent traction.

This is achieved easily with

the inversion table by creating

a rocking motion. Some

doctors contraindicate inversion

therapy for very good reasons.

In some cases they have not

taken the time to study this

simple

therapy that has

brought pain relief and

a better quality of life to

hundreds of thousands of people. |

|

| For

anyone about to begin a program

of

inversion therapy we offer a

few suggestions. |

Begin

slowly: Invert only 15 to 20

degrees at first, and stay inverted

only as long as it feels comfortable,

which may only be a few seconds at

first. Remarkably, you can gain all

of the benefits of inversion without

ever fully inverting yourself. Most

people find 20 to 60 degrees of decline

adequate and very comfortable.

Come

up slowly: When you come back upright

the pressure is again placed on the

discs and nerves. Come up slowly and

relax at the horizontal before coming

upright.

Make

changes gradually: Increase

the angle of incline only if it is

comfortable, and only increase the

angle a few degrees at a time. The

Hang Ups F5000 inversion table has

a tether strap to help people stay

within their inversion range. People

can add rocking back and forth (rhythmic

traction) to their inversion program

once they feel comfortable.

Pay

attention to your body: You're

unique, and your body will tell you

what's good for it. You determine

the pace when adapting to the inverted

world.

Relaxing

after a long day at a 25-45 degree

angle for 15-20 minutes can be a great

stress relieving & rejuvenating

experience.

Rhythmic

Intermittent Traction: Use

intermittent traction (pull and release)

or rhythmic traction to encourage

blood, lymph, and spinal fluid circulation.

Moving, twisting, stretching, and

light exercise while inverted aids

in the alignment of bones and organs

while minimizing any increase in blood

pressure, but strenuous exercise is

not recommended while inverted. Just

relax and enjoy!

Do

it regularly: There are a variety

of inversion programs and exercises.

Trust yourself to find the approach

that's best for you, and then do it

every day. Two or three short sessions

(10-20 minutes) a day seem to work

best for most people.

Inversion

is a very dynamic & effective

form of traction. Even

at a 45 degree angle a person is achieving

a greater force of pull on the back

than hospital traction. The

force of the pull registers much stronger

on the body than it does on the conscious

mind. This is why it iseasy to over

stretch the muscles & nerves of

the back and neck & possibly get

a spasm. Remember, most adults have

not hung upside down since they were

little kids.

After

using inversion for a while usually

the disc compression and nerve pain

is relieved enough to begin an exercise

program. Most people suffering

disc compression have a problem with

pelvic tilt

that adds to the malalignment of the

spine and nerve irritation. This pelvic

tilt problem and some exercises

are discussed on this page click

here:

Based

on years of research and the testimonials

of hundreds of people who have found

relief from back pain, inversion is

a powerful, natural option for people

who want to relieve lower back pain.

Sometimes there's an explanation for

why inversion works, and sometimes

there isn't - it works for some and

not for others. We only know that

for many people, literally turning

their world upside down through inversion

therapy can provide an alternative

to drugs and surgery in a life filled

with daily pain.

Many

people say it is the greatest stretch

they have had in years.

Dr.

Bernard Jensen who many consider to

be one of the greatest naturopathic

teachers and healers of the 20th century

recommends using a slant board as

part of an optimum health program.

This inversion

table does everything the slant board

does & more!!!

|

|

|